Notes collected from Daniel H. Pink's To Sell Is Human.

The balance has shipped. If you're a buyer and you've got just as much as information as the seller, along with the means to talk back, you're no longer the only one who needs to be on notice. In a world of information parity, the new guiding principle is caveat venditor--seller beware.

. . .

But the sharpest example is in plain view when you walk into the store. Each salesperson sits at a small desk--him on side, the customer on the other. Each desk also has a computer. In most settings, the seller would look at the computer screen and the buyer at the computer's backside. But here he computer is positioned not in front of either party, but off to the side with its screen facing outward so both buyer and seller can see it at the same time. It's the literal picture of information symmetry.

No haggling. Transparent commissions. Informed customers. Once again, it all sounds so enlightened. And maybe it is. But that's not why this new approach exists.

This is why: On Saturday I spent at SK Motors, a total of eight customers came in the entire day. On the Saturday at CarMax, more than that showed up in the first fifteen minutes.

. . .

Successful negotiators recommend that you should mimic the mannerisms of you negotiation partner to get a better deal. For example, when the other person rubs his/her face, you should, too. However, they say it is very important that you mimic subtly enough that the other person does not notice what you are doing, otherwise this technique completely backfires. Also, do not direct too much of your attention to the mimicking so you don't lose focus on the outcome of the negotiation. Thus, you should find a happy medium of consistent, but subtle mimicking that does not disrupt your focus.

. . .

One of Gueguen's studies found that women in nightclubs were more likely to dance with men who lightly touched their forearm for second or two when making the request. The same held in a non-nightclub setting, when men asked for women's phone numbers. (Yes, both studies took place in France.) In other research, when signature gatherers asked strangers to sign a petition, about 55 percent of people did so. But when the canvassers touched people once on the upper arm, the percentage jumped to 81 percent. Touching even proved helpful in our favorite setting: a used-car lot. When salesmen (all the sellers were male) lightly touched prospective buyers, those buyers rated them far more positively than they rated salespeople who didn't touch.

. . .

The notion that extraverts are the finest salespeople is so obvious that we've overlooked one teensy flaw. There's almost no evidence that it's actually true.

. . .

In other words, the salespeople with an optimistic explanatory style--who saw rejections as temporary rather than permanent, specific rather than universal, and external rather than personal--sold more insurance and survived in their job much longer. What's more, explanatory style predicted performance with about the same accuracy as the most widely used insurance industry assessment. It's a catalyst that can stir persistence, steady us during challenges, and stroke the confidence that we can influence our surroundings.

. . .

This theme eventually arises in almost any conversation about traditional sales. take, for example, ralph Chauvin, vice president of sales at Perfetti Van Melle, the Italian company that makes Mentos mints, AirHead fruit chews, and other delicacies. His sales force sells products to retailers who then stock their shelves and hope customers will buy. In the past few years he says he's seen a shift. Retailers are less interested in figuring out how many rolls of Mentos to order than in learning how to improve all facets of their operation. "They're looking for unbiased business partners," Chauvin told me. And that changes which salespeople are most highly prized. It isn't necessarily the "closers," those who can offer an immediate solution and secure the signature on the contract, he says. It's those "who can brainstorm with the retailers, who uncover new opportunities for them, and who realize that it doesn't matter if they close at that moment." Using a mix of number crunching and their own knowledge and expertise, the Perfetti salespeople tell retailers "what assortment of candy is the best for them to make the most money." That could mean offering five flavors of Mentos rather than seven. And it almost always means including products from competitors. In a sense, Chauvin says, his best salespeople think of their jobs not so much as selling candy but as selling insights about the confectionery business.

. . .

we often understand something better when we see it in comparison with something else than when we see it in isolation.

. . .

The lesson here is critical: The purpose of a pitch isn't necessarily to move others immediately to adopt your idea. The purpose is to offer something so compelling that it begings with a conversation, brings the other person in as a participant, and eventually arrives at an outcome that appeals to both of you. In a world where buyers have ample information and an array of choices, the pitch is often the first word, but it's rarely the last.

. . .

-Hand hygiene prevents you from catching diseases.

** Hand hygiene prevents patients from catching diseases.

-Gel in, wash out.

Clever signs alone won't eliminate hospital-acquired infections. As surgeon Atul Gawande has observed, checklists and other processes can be highly effective on this front. But Grant and Hofmann reveal something equally crucial: "Our findings suggest that health and safety messages should focus not on the self, but rather on the target group that is perceived as most vulnerable."

. . .

Children play here,

Pick up after your dog.

Monday, December 28, 2015

Wednesday, June 17, 2015

Холбоо Дөрвөн Туужийн Хосгүй Сонин Мөрүүд

Бөхийн Бааст гуайн Холбоо Дөрвөн Тууж нэртэй хосгүй сонин ном нэгэн байна. Цаг цагийн тохиолд эндээн хэд гурван өгүүлбэр тэрхүү сонин номноос тэмдэглэж авъя юу хэмээн санавай :)

Хоёр гэрийн цөөн бог мал хоёр үнээ их өтгийн хойт захын өндөр бургасыг оролцуулж зулзаган бургас огтолж сүлжсэн шарвин хэмээх задгай хашаанд хотолно.

Дахин тэгтлээ сүрхий хүйтэрсэн ч үгүй, цас ч бараг нэмж унасангүй, жирийн нам гүм өдрүүд гэзэг даран өнгөрсөөр...

Голын цоолго дээр овоорч ус уун, нимгэн хамхаг буюу үйрсэн мөс хэмлэн, чичирч дааран, биеэ агдайлган майлалдаж, шуугин гэрийн зүг уван цуван байсан хонь, ямааг мөчир гишүү цуглуулж явсан Думбаа чаа чүү гэж анир чимээ өгч туув. Хонь ямаа дагтаршсан цастай замаар тожир тожир хийн цувах мөртөө, цасан дороос цухуйсан өвс, цастай барилдаж хөлдсөн бургас улиасны хавчийг олзорхон түүнэ.

- Өнөө хоёр жаал, чиг ч үгүй, чимээ ч үгүй боллоо. Яадаг билээ гээч! гэхэд;

- Толгой хандсан тийш гүйсээр нэг мэдэхнээ нь газрын мухарт хүрчихэв дээ. Өвлийн хүйтэнд цааш нь явах сайхан, нааш нь эргэх амаргүй байдаг шүү гэж хэлсэн л юмсан. Ядахдаа муу хүү минь нимгэн заргастай яваа юмсан гэж Думбаа өгүүлэв.

- Өнөө хоёр минь юу ч болтугай айсуй, гүнгэр гүнгэр ярьчихсан их сүрхий шив дээ гэж Норов алгай өгүүлэхэд

"...Тэгэлгүй яахав!..." гэж зөвшин тогтоод гэр гэр лүүгээ салан одов.

Усгал зөөлөн харц, төв сайхан нүүрнээс нь тэр авгайг цайлган цагаан санаатай, яриа хөөрт дуртай, зочломтгой зантайгий нь шууд мэдэж болно.

Малчин хүмүүс гэдэг хязгааргүй хөх тэнгэрийн бүрхүүл дор нүд алдам мэлцийн цэлийсэн уудам хээр нутагт түг түмэн он улирлыг өмссөн хувцас мэт элээн өнгөрүүлэхдээ бичин бичээд баршгүй гайхамшгийн гайхамшигт бүхнийг ухаалан бүтээсээр иржээ.

Улаан харганыг цааш өнгөрөхөд дахин баахан зулзаган хүрэн бураатай газар хүрнэ. Тэр газрыг Шарвинт гэнэ.

Мод бүр сэгсийж бурзайсан буурал цанд хучигдаад элгээ тэвэрсэн хүн шиг атиралдаж мушгиралдан хөлдсөн мөчир гишүүнээс нь салхины цаг цагийн үлээлтэд хөлдүү нулимс мэт хөвсгөр цас газарт харамчихнаар унаж байв. Салхи бүр хүчтэй хөдөлбөл бургасны мөчир туниатай нь аргагүй чичигнэн хөдөлж моддын салхинд исгэрэх чимээ заримдаа ууль шувууны өлзийгүй дууг санагдуулна.

Хоёр гэрийн цөөн бог мал хоёр үнээ их өтгийн хойт захын өндөр бургасыг оролцуулж зулзаган бургас огтолж сүлжсэн шарвин хэмээх задгай хашаанд хотолно.

. . .

Дахин тэгтлээ сүрхий хүйтэрсэн ч үгүй, цас ч бараг нэмж унасангүй, жирийн нам гүм өдрүүд гэзэг даран өнгөрсөөр...

. . .

Голын цоолго дээр овоорч ус уун, нимгэн хамхаг буюу үйрсэн мөс хэмлэн, чичирч дааран, биеэ агдайлган майлалдаж, шуугин гэрийн зүг уван цуван байсан хонь, ямааг мөчир гишүү цуглуулж явсан Думбаа чаа чүү гэж анир чимээ өгч туув. Хонь ямаа дагтаршсан цастай замаар тожир тожир хийн цувах мөртөө, цасан дороос цухуйсан өвс, цастай барилдаж хөлдсөн бургас улиасны хавчийг олзорхон түүнэ.

. . .

- Өнөө хоёр жаал, чиг ч үгүй, чимээ ч үгүй боллоо. Яадаг билээ гээч! гэхэд;

- Толгой хандсан тийш гүйсээр нэг мэдэхнээ нь газрын мухарт хүрчихэв дээ. Өвлийн хүйтэнд цааш нь явах сайхан, нааш нь эргэх амаргүй байдаг шүү гэж хэлсэн л юмсан. Ядахдаа муу хүү минь нимгэн заргастай яваа юмсан гэж Думбаа өгүүлэв.

. . .

- Өнөө хоёр минь юу ч болтугай айсуй, гүнгэр гүнгэр ярьчихсан их сүрхий шив дээ гэж Норов алгай өгүүлэхэд

. . .

"...Тэгэлгүй яахав!..." гэж зөвшин тогтоод гэр гэр лүүгээ салан одов.

. . .

Усгал зөөлөн харц, төв сайхан нүүрнээс нь тэр авгайг цайлган цагаан санаатай, яриа хөөрт дуртай, зочломтгой зантайгий нь шууд мэдэж болно.

. . .

Малчин хүмүүс гэдэг хязгааргүй хөх тэнгэрийн бүрхүүл дор нүд алдам мэлцийн цэлийсэн уудам хээр нутагт түг түмэн он улирлыг өмссөн хувцас мэт элээн өнгөрүүлэхдээ бичин бичээд баршгүй гайхамшгийн гайхамшигт бүхнийг ухаалан бүтээсээр иржээ.

. . .

Улаан харганыг цааш өнгөрөхөд дахин баахан зулзаган хүрэн бураатай газар хүрнэ. Тэр газрыг Шарвинт гэнэ.

. . .

Мод бүр сэгсийж бурзайсан буурал цанд хучигдаад элгээ тэвэрсэн хүн шиг атиралдаж мушгиралдан хөлдсөн мөчир гишүүнээс нь салхины цаг цагийн үлээлтэд хөлдүү нулимс мэт хөвсгөр цас газарт харамчихнаар унаж байв. Салхи бүр хүчтэй хөдөлбөл бургасны мөчир туниатай нь аргагүй чичигнэн хөдөлж моддын салхинд исгэрэх чимээ заримдаа ууль шувууны өлзийгүй дууг санагдуулна.

Стрес Менежмент

Шэйн Пэрришийн Farnam Street блогийг би бээр ихэд сонирхон ажиж явдаг ба өнөөдөр түүний Stress Management хэмээх богино постыг амтархан уншсанаа, өдрийн цай уух зуураа энд ийн орчууллаа.

Танхим дүүрэн хүмүүст стрес менежментийн талаар нэгэн сэтгэлзүйч хичээл заах ажээ. Түүнийг стакантай ус гартаа өргөхөд, сонсогчид өнөө улиг болсон "хагас хоосон, хагас дүүрэн" маягийн асуулт асуух нь гэж бодож. Гэтэл мань хүн малийтал инээмсэглэснээ, "Энэ стакантай ус хэр хүнд гэж бодож байна?" хэмээн тэднээс асуув.

Сонсогчид 200-аас 500 грам хооронд янзан бүрийн жин хэлвэй.

Сэтгэлзүйч ийн хэлэв: "Абсолют жин ямар байх нь ердөө чухал биш. Харин хэр удаан өргөх вэ гэдэгт л асуудлын зангилаа байна. Нэг минут энэ усыг өргө өө гэвэл, тэрэн шиг амархан зүйл байхгүй, өргөж л орхино. Харин нэг цаг өргөөдөхсөний дараа гар нэлээд бадайрч ирэх байх. Даамаа бүр бүтэн өдөр өргөвөл нь ёстой тамирдаад, гар тасарч унана биз дээ? Усны жин эдгээр туршилтын аль алинд нь яг ижилхэн байсан ч, өргөөд удах тусам бидэнд улам хүнд болохыг хэн ч төвөггүй баталж чадна." Танхимын голоор холхингоо тэрээр ийн үргэлжлүүлэв: "Бидний стресс, уур бухимдал яг энэ станкантай устай адил. Хэдэн секунд бодоод үз, сүйдтэй юм энд юу ч алга. Хэдэг цаг үргэлжлүүлээд бод, шаналгаа болж эхлэнэ ээ дээ? Одоо харин бүтэн өдөр зөвхөн нөгөөхөө бод доо, ухаан санаа бачуураад, юу ч хийж чадах аа болино оо доо?"

Стрес бухимдлаа тайлж, таягдан хаяж чаддаг байх хэрэгтэй, хүмүүс ээ! Аль болох орой болохоос өмнө ачаа бухимдлаа буулгаж бай, орондоо хамт аваад орох тухай ер нь бол бодох ч хэрэггүй. Стакантай усаа зүгээр л хаа нэг газар тавьж орхи!

Танхим дүүрэн хүмүүст стрес менежментийн талаар нэгэн сэтгэлзүйч хичээл заах ажээ. Түүнийг стакантай ус гартаа өргөхөд, сонсогчид өнөө улиг болсон "хагас хоосон, хагас дүүрэн" маягийн асуулт асуух нь гэж бодож. Гэтэл мань хүн малийтал инээмсэглэснээ, "Энэ стакантай ус хэр хүнд гэж бодож байна?" хэмээн тэднээс асуув.

Сонсогчид 200-аас 500 грам хооронд янзан бүрийн жин хэлвэй.

Сэтгэлзүйч ийн хэлэв: "Абсолют жин ямар байх нь ердөө чухал биш. Харин хэр удаан өргөх вэ гэдэгт л асуудлын зангилаа байна. Нэг минут энэ усыг өргө өө гэвэл, тэрэн шиг амархан зүйл байхгүй, өргөж л орхино. Харин нэг цаг өргөөдөхсөний дараа гар нэлээд бадайрч ирэх байх. Даамаа бүр бүтэн өдөр өргөвөл нь ёстой тамирдаад, гар тасарч унана биз дээ? Усны жин эдгээр туршилтын аль алинд нь яг ижилхэн байсан ч, өргөөд удах тусам бидэнд улам хүнд болохыг хэн ч төвөггүй баталж чадна." Танхимын голоор холхингоо тэрээр ийн үргэлжлүүлэв: "Бидний стресс, уур бухимдал яг энэ станкантай устай адил. Хэдэн секунд бодоод үз, сүйдтэй юм энд юу ч алга. Хэдэг цаг үргэлжлүүлээд бод, шаналгаа болж эхлэнэ ээ дээ? Одоо харин бүтэн өдөр зөвхөн нөгөөхөө бод доо, ухаан санаа бачуураад, юу ч хийж чадах аа болино оо доо?"

Стрес бухимдлаа тайлж, таягдан хаяж чаддаг байх хэрэгтэй, хүмүүс ээ! Аль болох орой болохоос өмнө ачаа бухимдлаа буулгаж бай, орондоо хамт аваад орох тухай ер нь бол бодох ч хэрэггүй. Стакантай усаа зүгээр л хаа нэг газар тавьж орхи!

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

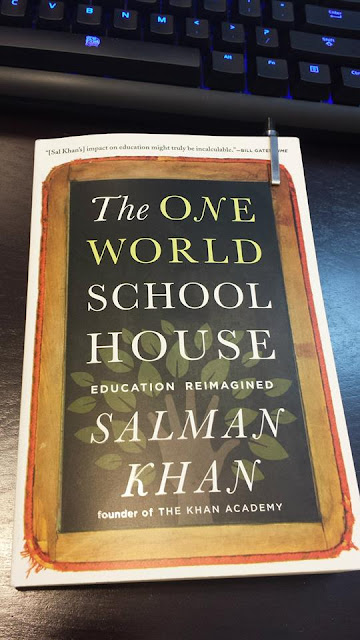

The One World School House: Education Reimagined

Personal notes collected from a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful work and great thought distillation from Salman Khan: The One World School House--Education ReImagined.

We are still in the early stage of an inflection point that I believe is the most consequential in history: the Information Revolution. And in this revolution, the pace of change is swift that deep creativity and analytical thinking are no longer optional; they not luxuries but survival skills.

I'd had plenty of professors who knew their subject cold but simply weren't good at sharing what they knew. I believed, and still believe, that teaching is a separate skill--in fact, an art that is creative, intuitive, and highly personal.

But it isn't only an art. It has, or should have, some of the rigor of science as well.

Unfortunately, however, the idea that smaller classes alone will magically solve the problem of students being left behind is fallacy.

It ignores several basic facts about how people actually learn. People learn at different rates. Some people seem to catch on to things quick bursts of intuition; others grunt and grind their way toward comprehension. Quicker isn't necessarily smarter and slower definitely isn't dumber. Further, catching on quickly isn't the same as understanding thoroughly. So the pace of learning is a question of style, not relative intelligence. The tortoise may very well end up with more knowledge--more useful, lasting knowledge--than the hare.

Moreover, a student who is slow at learning arithmetic may be off the charts when it comes to the abstract creativity needed in higher mathematics. The point is that whether there are ten or twenty kids in a class, there will be disparities in their grasp of a topic at any given time. Even a one-to-one ratio is not ideal if the teacher feels forced to march the student along at a state-mandated pace, regardless of how well the concepts are understood. When that rather arbitrary "snapshot" moment comes along--when it's time to wrap up the module, give the exam, and move on--there will still like be some students who haven't quite figured things out.

They could probably figure things out eventually--but that's exactly the problem. The standard classroom model doesn't really allow for eventual understanding. The class--of whatever size--has moved on.

I was starting to get seriously concerned that perhaps I was doing Nadia more harm than good. With nothing but kind inventions, I was causing her a lot of discomfort and anxiety. My hope had been to restore her confidence; maybe I was damaging it still further.

This forced me to acknowledge that sometimes the presence of a teacher--either in the room or at the other end of a telephone connection; either in a class of thirty or tutoring one-to-one--can be a source of student paralysis. From the teacher's perspective, what's going on is a helping relationship; but from the student's point of view, it's difficult if not impossible to avoid an element of confrontation. A question is asked; an answer is expected immediately; that brings pressure. The student doesn't want to disappoint the teacher. She fears she will be judged. And all these factors interfere with the student's ability to fully concentrate on the matter at hand. Even more, students are embarassed to communicate what they do and do and do not understand.

In a traditional academic model, the time allotted to learn something is fixed while the comprehension of the concept is variable. Washburne was advocating the opposite. What should be fixed is a high level of comprehension and what should be variable is the amount of time students have to understand a concept.

Stressing passivity over activity is one such misstep. Another, equally important, is the failure of standard education to maximize brain's capacity for associative learning--the achieving of deeper comprehension and more durable memory by relating something newly learned to something already known.

As Kandel writes, "For a memory to persist, the incoming information must be thoroughly and deeply processed. This is accomplished by attending to the information and associating it meaningfully systematically with knowledge already well established in memory."

In other words, it's easier to understand and remember something if we can relate it to something else we already know. This is why it's easier to memorize a poem than a series of non-sense syllables of equal length. In a poem, each word relates to images in our minds and to what has come before; there are rules of rhythm and connection that we understand, even if subliminally, the poem must follow. Rather than memorizing individual bits of information, we are dealing with patterns and strands of logic that allow us to come closer to seeing something whole.

The possibilities are endless, but they can't be realized given the balkanizing habits of our current system. Even within the already sawed-off classes, content is chunked into stand-alone episodes, and the connections are severed. In algebra, for example, students are taught to memorize the formula for the vertex of a parabola. Then they separately memorize the quadratic formula. In yet another lesson, they probably learn to "complete the square." The reality, however, is that all those formulas are expressions of essentially the same mathematical logic, so why aren't they taught together as the multiple facets of the same concept?

I am not just nitpicking here. I believe that the breaking up of concepts like these has profound and even crucial consequences for how deeply students lean and how well they remember it. It is the connections among concepts--or the lack of connections--that separate the students who memorize a formula for an exam only to forget it the next month and the same students who internalize the concepts and are able to app-ly them when they need them a decade later.

The heavy baggage of the current academic model has become increasingly apparent recently, as economic realities no longer favor a docile and disciplined working class with just the basic proficiencies in reading, math, and the liberal arts. Today's world needs a workforce of creative, curious, and self-directed lifelong learners who are capable of conceiving and implementing novel ideas. Unfortunately, this is the type of student that the Prussian model suppresses.

Let's consider a few things about that inevitable test. What constitutes a passing grade? In most classrooms in most schools, students pass with 75 or 80 percent. This is customary. But if you think about it even for a moment, it's unacceptable if not disastrous. Concepts build on one another. Algebra requires arithmetic. Trigonometry flows from geometry. Calculus and physics call for all of the above. A shaky understanding early on will lead to complete bewilderment later. And yet we blithely give out passing grades for test scores of 75 or 80. For many teachers, it may seem like a kindness or perhaps merely an administrative necessity to pass these marginal students. In effect, it is a disservice and a lie. We are telling students they've learned something that they really haven't learned. We wish them and nudge them ahead to the next, more difficult unit, for which they have not been properly prepared. We are setting them up to fail.

She's been a "good" math student all along, but all of a sudden, no matter how much she studies and how good her teacher is, she has trouble comprehending what is happening in class.

How is this possible? She's gotten A's. She's been in the top quintile of her class. And yet her preparation lets her down. Why? The answer is that our student has been a victim of Swiss cheese learning. Though it seems solid from outside, her education is full of holes.

Once a certain level of proficiency is obtained, the learner should attempt to teach the subject to other students so that they themselves develop a deeper understanding. As they progress, they should keep revisiting the core ideas through the lenses of different, active experiences. That's the way to get the holes out of Swiss cheese learning. It is, after all, much better and much more useful to have a deep understanding of algebra than a superficial understanding of algebra, trigonometry, and calculus. Students with deep backgrounds in algebra find calculus intuitive.

The example of the historically good student all of a sudden not understanding an advanced class because of Swiss cheese foundation could best be termed hitting a wall. And it is commonplace. We have all seen classmates go through this and have directly experienced it ourselves. It's a horrible feeling, leaving the student only frustration and helplessness.

But absent a firm grasp of the basics, organic chemistry doesn't feel intuitive at all; rather, it seems like a daunting dizzying, and endless progression of reactions that need to be memorized. Faced with such a mind-numbing chore, many students give up. Some, by superhuman effort, power through. The problem is that memorization without intuitive understanding can't remove the wall, but only push it back.

Calculus has the power to solve problems that are beyond the reach of more elementary forms of math, but unless you've truly understood those more elementary concepts, calculus of no use to you. It's this element of synthesis, of pulling it all together, that gives calculus its beauty. At the same time, however, it's why calculus is so likely to reveal the cracks in people's math foundations. In stacking concepts upon concept, calculus is the subject most likely to tip the balance, reveal the dry rot, and send the whole edifice crashing down.

Now, I tell this story not to embarrass or criticize the CFO. He was a bright guy with Ivy League education, and his math background extended to calculus and beyond. Clearly though, there seemed to be something wrong, something missing, in the way that he'd been taught. He'd apparently studied algebra with an eye toward getting a good grade on the test that was the climax of the unit; presumably the test centered on the working out of a handful problems, and the problems consisted of solving for variables that had no apparent meaning in the real world. What, then, was the point of learning algebra? What was algebra about? What could algebra do? There very basic questions, it seemed, had gone unexplored.

This failure to relate classroom topics to their eventual application in the real world is one of the central shortcomings of our broken classroom model, and is a direct consequence of our habit of rushing through conceptual modules and pronouncing them finished when in fact only a very shallow level of functional understanding has been reached. What do most kids actually take away from algebra? Sadly, the usual takeaway is that it's about a bunch of x's and y's, and that if you plug in a few formulas and procedures that you've learned by rote, you'll come up with the answer.

But the power and importance of algebra is not to be found in x's and y's on a test paper. The important and wonderful diverse set of phenomena and ideas. The same equations that I used to figure out the production costs of a public company could be used to calculate the momentum of a particle in space. The same equations can model both the optimal path of a projectile and the optimal price for a new product. The same ideas that govern the changes of inheriting a disease also informs whether it makes sense to go for a first down on fourth-and-inches.

The difficulty, of course, is that getting to this deeper, functional understanding would use up valuable class time that might otherwise be devoted to preparing for a test. So most students, rather than appreciating algebra as a keen and versatile tool for navigating through the world, see it as one more hurdle to be passed, a class rather than a gateway. The learn it, sort of, then push it aside to make room for the lesson to follow.

For all of that, conventional schools tend to place great emphasis on test results as a measure of a student's innate ability or potential--not only on standardized tests, but on thoroughly unstandardized end-of-term exams that may or may not be well designed--and this has very serious consequences. What are we actually accomplishing when we hand out those A's and B's and C's and D's? As we've seen, what we're not accomplishing is meaningfully measuring student potential. On the other hand, what we're doing very effectively is labeling kids, squeezing them into categories, defining and often limiting their futures.

Let's stay for a moment with this notion of differentness when it comes to problem-solving. Isn't this simply another way of defining creativity? In my view, that's exactly what it is, and the troubling fact is that our current system of testing and grading tends to filter out the creative, different-thinking people who are most likely to make major contributions to a field.

The truth is that anything significant that happens in math, science, or engineering is the result of heightened intuition and creativity. The is art by another name, and it's something that tests are not very good at identifying or measuring. The skills and knowledge that tests can measure are merely warm-up exercises.

The danger of using assessments as reasons to filter out students, then, is that we may overlook or discourage those whose talents are of a different order--whose intelligence tends more to the oblique and the intuitive. At the very least, when we use testing to exclude, we run the risk of squelching creativity before it has a chance to develop.

According to a journal article called "Teacher Assessment of Homework," by a researcher named Stephen Alioa, the rather surprising fact was that "most teachers do not take courses specifically on homework during teacher training." Lesson plans, yes; techniques for guiding classroom activities, yes; homework, no. It's as if homework is an afterthought, some strange gray area that is still the responsibility of students but not so much for teachers. According to Harris Cooper, author of The Battle over Homework, when it comes to crafting homework assignments, "most teachers are winging it." No wonder homework is sometimes seen by students--and parents--as a tedious waste of time.

On the other hand, when homework is demanding and meaningful, some students, at least, appreciate the difference. One high school junior commendted in the Times blog that "at my old school, I got a lot more homework. At my new prep school I get less. The difference: I spend much more time on my homework at my current school because it is harder. I feel as if I actually accomplish something with the harder homework."

This sentiment was echoed by the same seventh grader who complained about being up until midnight every night. "We should be getting harder work, not more work!"

But the more interesting question is why we have adopted this pile-it-on mentality in the first place. There is a swinging pendulum when it comes to attitudes about homework, and that pendulum has been in more or less constant motion for at least a hundred years. At the dawn of the twentieth century, the main purpose of homework was thought to be "training the mind" for the largely clerical, repetitive kinds of job that the trend toward urbanization and office work required; thus the emphasis was on memory drills, pattern recognition, rules of grammar--things that disciplined the mind but did not necessarily expand it.

For many if not most families, time together has become an increasingly rare and precious commodity. Moms work. Adults travel on business. Kids confront an ever wider array of distractions and so-called social media whose net effect, ironically enough, is to make people less social, more head-down on their keyboards and keypads.

So then, is doing homework really the best use of time that families might otherwise spend just being together? Studies suggest otherwise. One large survey conducted by the University of Michigan concluded that the single strongest predictor of better achievement scores and fewer behavioral problems was not time spent on homework, but rather frequency and duration of family meals. If we think about it, this really shouldn't be surprising. When families actually sit down and talk--when parents and children exchange ideas and truly show an interest in each other--kids absorb values, motivation, self-esteem; in short, they grow in exactly those attributes and attitudes that will make them enthusiastic and attentive learners. This is more important than mere homework.

Even with the homework help is indirect, households with books and families with a tradition of educational success have an unfair edge. Wealthier kids are less likely to be burdened with after-school jobs or chores that single parents--or exhausted parents--can't perform. In short, homework contributes to an unlevel playing field in which, educationally speaking, the rich get richer and poor get poorer.

As we've seen, students learn at different rates. Attention spans tend to max out at around fifteen minutes. Active learning creates more durable neural pathways than passive learning. Yet the passive in-class lecture--in which the entire class is expected to absorb information at the same rate, for fifty minutes or an hour, while sitting still and silent in their chairs--remains our dominant teaching mode. This results in the majority of students being lost or bored at any given time, even when there is a great lecturer.

First, I believe that the primary reason why most students don't complete their homework is frustration. They don't understand the material and no one is there to help and give feedback.

Now like everyone else involved in our education debates, I feel that money devoted to learning is money well spent--especially compared to the vast sums of squandered on military contracting, farm subsidies, bridges to nowhere, and so forth. Still, waste in certain areas of our public life does not justify waste in others, and the sad truth is that a significant part of what we spend on education is just that--waste. We spend lavishly but not wisely. We obsess about more because we cannot envision or agree about better.

For example, student/teacher ration is important. Obviously, the fewer students per teacher, the more attention each student will get. But isn't the student-to-valuable-time-with-the-teacher ratio important? I have sat in eight-person college seminars where I never had a truly meaningful interaction with the professor; I have been in thirty-person classrooms where the teacher took a few minutes to work with me and mentor me directly on a regular basis.

What will make this goal attainable is the enlightened use of technology. Let me stress ENLIGHTENED use. Clearly, I believe that technology-enhanced teaching and learning is our best chance for an affordable and equitable educational future. But the key question is how the technology is used. It's not enough to put a bunch of computers and smartboards into classrooms. The idea is to integrate the technology into how we teach and learn; without meaningful and imaginative integration, technology in the classroom could turn out to be just one more very expensive gimmick.

So the next step in the refinement of the software was to devise a hierarchy or web of concepts--the "knowledge map" we've already seen--so that the system itself could advise students what to work on next.

I eventually formed the conviction that my cousins--and all students--needed higher expectations to be placed on them. Eighty or 90 percent is okay, but I wanted them to work on things until they could get ten right answers in a row. That may sound radical or overidealistic or just too difficult, but I would argue that it was the only simple standard that was truly respectful of both the subject matter and the students. (We have refined the scoring details a good bit since then, but the basic philosophy hasn't changed.) It's demanding, yes. But it doesn't set students up to fail; it sets them up to succeed--because they can keep trying until they reach this high standard.

I happen to believe that every student, given the tool and the help that he or she needs, can reach this level of proficiency in basic match and science. I also believe it is a disservice to allow students to advance without this level of proficiency because they'll fall on their faces sometime later.

In particular, she was spending inordinate amount of time wrestling with the concepts of adding and subtracting negative numbers; she was about stuck as stuck could get. Then something clicked. I don't know exactly how it happened, and neither did her classroom teacher; that's part of the wonderful mystery of human intelligence.

They asked me to write a proposal for what I would do with $2 million; nothing to involved; two pages would do. A million dollars per page; not bad. Keep in mind that up to this point I had spend a grand total of about $2,000 on the Khan Academy.

In itself this was not so unusual. Many people had already donated $5, $10, and even $100 at a time over PayPal. But this time a check for $10,000 arrived in the mail. The sender was named Ann Doerr. After a little frantic web research, I realized that Ann was the wife of famed venture caplitalist John Doerr. I sent her an email thanking her for her generous support, and she wrote back suggesting we have lunch.

We agreed to meet in May in downtown Palo Alto. Ann arrived on a green-blue bicycle. We talked about what Khan Academy could be. When Ann asked how I was supporting myself and my family, I answered, trying not to sound too desperate, "I'm not; we're living off of savings." She nodded and we each went our way.

About twenty minutes later, I got a text message I was parking in my driveway. It was from Ann: You need to support yourself. I am sending a check for $100,000 right now.

I almost crashed into the garage door.

Anyone who stops learning is old, whether twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning stays young. The greatest thing in life is to keep your mind young.

It is utterly false and cruelly arbitrary to put all the play and learning into childhood, all the work into middle age, and all the regrets into old age.

New knowledge becomes a smaller and smaller part of the mix. The problem is that as the pace of change accelerates all around us, the ability to learn new things may be the most important skill of all. Is it realistic to expect adults to be able to do this?

The answer is resounding yes. According to a recent paper issued by the Royal Society of London, "the brain has extraordinary adaptability, sometimes referred as 'neuroplasticity.' This is due to the process by which connections between neurons are strengthened when they are simultaneously activated; often summarized as, 'neurons that fire together wire together.' The effect is known as experience-dependent plasticity and is present throughout life."

On the other hand, adults seem to be better at learning by association. Weith a bigger knowledge base to begin with, and long-established habits of logic and deduction, grown-ups are more likely to grasp new concepts by way of their connections to ideas already known.

The certainty of change, coupled with the complete uncertainty as to the precise nature of the change, has profound and complex implications for our approach to education. For me, though, the most basic takeaway is crystal clear: Since we can't predict exactly what today's young people will need to know in ten or twenty years, what we teach them is less important than how they learn to teach themselves.

Coming back to MIT, Shantanu and I did take something close to double course load, and we both graduated with high honor GPAs and multiple degrees. And it wasn't because we were any smarter or harder-working than our peers. It was because we didn't waste time sitting passively in class.

To state what should be obvious, there is nothing natural about segregating kids by age.

In fact, the only way to do it would be to make clear that what happens in the classroom is but preparation for real competition in the outside world. That the exams aren't there to label and humiliate you; they are there to fine-tune your abilities. That when you identified deficiencies, it doesn't mean that you are dumb; it means that you have something to work on.

As everyone knows, it's easier to keep pedaling a bicycle than to start one again after a stop; why should the process be any different with learning?

In point of fact, however, the most serious downside of summer vacation isn't just that kids stop learning; it's that they almost immediately start unlearning.

But I note that I say preparedness, not potential! Well-designed tests can give a pretty solid idea of what a student has learned, but only a very approximate picture of what she can learn. To put in a slightly different way, tests tend to measure quantities of information (and sometimes knowledge) rather than quality of minds--not to mention character.

First, I would eliminate letter grades altogether. In a system based on mastery learning, there is no need and no place for them. Students advance only when they demonstrate clear proficiency with a concept, as measured either by the ten-in-a-row heuristic or some future refinement of it. Since no one is pushed ahead (or left behind) until proficiency is reached, the only possible grade would be an A. To paraphrase Garrison Keillor, all the kids would be way above average, so grades would be pointless.

For one thing, Waterloo recognized the value of internships long ago (they call them co-ops) and has made them an integral part of students' experience. By graduation, a typical Waterloo grad will have spent six internships lasting a combined twenty-four months at a major companies--often American. The typical American grad will have spent about thirty-six months in lecture halls and a mere three to six months in internships.

The school I envision would embrace technology not for its own sake, but as a means to improve deep conceptual understanding, to make quality, relevant education far more portable, and--somewhat counterintuitively--to humanize the classroom. It would raise both the status and the morale of teachers by freeing them from drudgery and allowing them more time to teach, to help. It would give students more independence and control, allowing them to claim true ownership of their educations. By mixing ages and encouraging peer-to-peer tutoring, his schoolhouse would give adolescents the chance to begin to take on adult responsibilities.

Lessons aimed at thorough master of concepts--interrelated concepts--would proceed in harmony with the way our brains are actually wired, and would prepare students to function in a complex world where good enough no longer is.

We are still in the early stage of an inflection point that I believe is the most consequential in history: the Information Revolution. And in this revolution, the pace of change is swift that deep creativity and analytical thinking are no longer optional; they not luxuries but survival skills.

. . .

I'd had plenty of professors who knew their subject cold but simply weren't good at sharing what they knew. I believed, and still believe, that teaching is a separate skill--in fact, an art that is creative, intuitive, and highly personal.

But it isn't only an art. It has, or should have, some of the rigor of science as well.

. . .

Unfortunately, however, the idea that smaller classes alone will magically solve the problem of students being left behind is fallacy.

It ignores several basic facts about how people actually learn. People learn at different rates. Some people seem to catch on to things quick bursts of intuition; others grunt and grind their way toward comprehension. Quicker isn't necessarily smarter and slower definitely isn't dumber. Further, catching on quickly isn't the same as understanding thoroughly. So the pace of learning is a question of style, not relative intelligence. The tortoise may very well end up with more knowledge--more useful, lasting knowledge--than the hare.

Moreover, a student who is slow at learning arithmetic may be off the charts when it comes to the abstract creativity needed in higher mathematics. The point is that whether there are ten or twenty kids in a class, there will be disparities in their grasp of a topic at any given time. Even a one-to-one ratio is not ideal if the teacher feels forced to march the student along at a state-mandated pace, regardless of how well the concepts are understood. When that rather arbitrary "snapshot" moment comes along--when it's time to wrap up the module, give the exam, and move on--there will still like be some students who haven't quite figured things out.

They could probably figure things out eventually--but that's exactly the problem. The standard classroom model doesn't really allow for eventual understanding. The class--of whatever size--has moved on.

. . .

This forced me to acknowledge that sometimes the presence of a teacher--either in the room or at the other end of a telephone connection; either in a class of thirty or tutoring one-to-one--can be a source of student paralysis. From the teacher's perspective, what's going on is a helping relationship; but from the student's point of view, it's difficult if not impossible to avoid an element of confrontation. A question is asked; an answer is expected immediately; that brings pressure. The student doesn't want to disappoint the teacher. She fears she will be judged. And all these factors interfere with the student's ability to fully concentrate on the matter at hand. Even more, students are embarassed to communicate what they do and do and do not understand.

. . .

In a traditional academic model, the time allotted to learn something is fixed while the comprehension of the concept is variable. Washburne was advocating the opposite. What should be fixed is a high level of comprehension and what should be variable is the amount of time students have to understand a concept.

. . .

Stressing passivity over activity is one such misstep. Another, equally important, is the failure of standard education to maximize brain's capacity for associative learning--the achieving of deeper comprehension and more durable memory by relating something newly learned to something already known.

. . .

As Kandel writes, "For a memory to persist, the incoming information must be thoroughly and deeply processed. This is accomplished by attending to the information and associating it meaningfully systematically with knowledge already well established in memory."

In other words, it's easier to understand and remember something if we can relate it to something else we already know. This is why it's easier to memorize a poem than a series of non-sense syllables of equal length. In a poem, each word relates to images in our minds and to what has come before; there are rules of rhythm and connection that we understand, even if subliminally, the poem must follow. Rather than memorizing individual bits of information, we are dealing with patterns and strands of logic that allow us to come closer to seeing something whole.

. . .

The possibilities are endless, but they can't be realized given the balkanizing habits of our current system. Even within the already sawed-off classes, content is chunked into stand-alone episodes, and the connections are severed. In algebra, for example, students are taught to memorize the formula for the vertex of a parabola. Then they separately memorize the quadratic formula. In yet another lesson, they probably learn to "complete the square." The reality, however, is that all those formulas are expressions of essentially the same mathematical logic, so why aren't they taught together as the multiple facets of the same concept?

I am not just nitpicking here. I believe that the breaking up of concepts like these has profound and even crucial consequences for how deeply students lean and how well they remember it. It is the connections among concepts--or the lack of connections--that separate the students who memorize a formula for an exam only to forget it the next month and the same students who internalize the concepts and are able to app-ly them when they need them a decade later.

. . .

The heavy baggage of the current academic model has become increasingly apparent recently, as economic realities no longer favor a docile and disciplined working class with just the basic proficiencies in reading, math, and the liberal arts. Today's world needs a workforce of creative, curious, and self-directed lifelong learners who are capable of conceiving and implementing novel ideas. Unfortunately, this is the type of student that the Prussian model suppresses.

. . .

Let's consider a few things about that inevitable test. What constitutes a passing grade? In most classrooms in most schools, students pass with 75 or 80 percent. This is customary. But if you think about it even for a moment, it's unacceptable if not disastrous. Concepts build on one another. Algebra requires arithmetic. Trigonometry flows from geometry. Calculus and physics call for all of the above. A shaky understanding early on will lead to complete bewilderment later. And yet we blithely give out passing grades for test scores of 75 or 80. For many teachers, it may seem like a kindness or perhaps merely an administrative necessity to pass these marginal students. In effect, it is a disservice and a lie. We are telling students they've learned something that they really haven't learned. We wish them and nudge them ahead to the next, more difficult unit, for which they have not been properly prepared. We are setting them up to fail.

. . .

She's been a "good" math student all along, but all of a sudden, no matter how much she studies and how good her teacher is, she has trouble comprehending what is happening in class.

How is this possible? She's gotten A's. She's been in the top quintile of her class. And yet her preparation lets her down. Why? The answer is that our student has been a victim of Swiss cheese learning. Though it seems solid from outside, her education is full of holes.

. . .

Once a certain level of proficiency is obtained, the learner should attempt to teach the subject to other students so that they themselves develop a deeper understanding. As they progress, they should keep revisiting the core ideas through the lenses of different, active experiences. That's the way to get the holes out of Swiss cheese learning. It is, after all, much better and much more useful to have a deep understanding of algebra than a superficial understanding of algebra, trigonometry, and calculus. Students with deep backgrounds in algebra find calculus intuitive.

. . .

The example of the historically good student all of a sudden not understanding an advanced class because of Swiss cheese foundation could best be termed hitting a wall. And it is commonplace. We have all seen classmates go through this and have directly experienced it ourselves. It's a horrible feeling, leaving the student only frustration and helplessness.

. . .

But absent a firm grasp of the basics, organic chemistry doesn't feel intuitive at all; rather, it seems like a daunting dizzying, and endless progression of reactions that need to be memorized. Faced with such a mind-numbing chore, many students give up. Some, by superhuman effort, power through. The problem is that memorization without intuitive understanding can't remove the wall, but only push it back.

. . .

Calculus has the power to solve problems that are beyond the reach of more elementary forms of math, but unless you've truly understood those more elementary concepts, calculus of no use to you. It's this element of synthesis, of pulling it all together, that gives calculus its beauty. At the same time, however, it's why calculus is so likely to reveal the cracks in people's math foundations. In stacking concepts upon concept, calculus is the subject most likely to tip the balance, reveal the dry rot, and send the whole edifice crashing down.

. . .

Now, I tell this story not to embarrass or criticize the CFO. He was a bright guy with Ivy League education, and his math background extended to calculus and beyond. Clearly though, there seemed to be something wrong, something missing, in the way that he'd been taught. He'd apparently studied algebra with an eye toward getting a good grade on the test that was the climax of the unit; presumably the test centered on the working out of a handful problems, and the problems consisted of solving for variables that had no apparent meaning in the real world. What, then, was the point of learning algebra? What was algebra about? What could algebra do? There very basic questions, it seemed, had gone unexplored.

This failure to relate classroom topics to their eventual application in the real world is one of the central shortcomings of our broken classroom model, and is a direct consequence of our habit of rushing through conceptual modules and pronouncing them finished when in fact only a very shallow level of functional understanding has been reached. What do most kids actually take away from algebra? Sadly, the usual takeaway is that it's about a bunch of x's and y's, and that if you plug in a few formulas and procedures that you've learned by rote, you'll come up with the answer.

But the power and importance of algebra is not to be found in x's and y's on a test paper. The important and wonderful diverse set of phenomena and ideas. The same equations that I used to figure out the production costs of a public company could be used to calculate the momentum of a particle in space. The same equations can model both the optimal path of a projectile and the optimal price for a new product. The same ideas that govern the changes of inheriting a disease also informs whether it makes sense to go for a first down on fourth-and-inches.

The difficulty, of course, is that getting to this deeper, functional understanding would use up valuable class time that might otherwise be devoted to preparing for a test. So most students, rather than appreciating algebra as a keen and versatile tool for navigating through the world, see it as one more hurdle to be passed, a class rather than a gateway. The learn it, sort of, then push it aside to make room for the lesson to follow.

. . .

For all of that, conventional schools tend to place great emphasis on test results as a measure of a student's innate ability or potential--not only on standardized tests, but on thoroughly unstandardized end-of-term exams that may or may not be well designed--and this has very serious consequences. What are we actually accomplishing when we hand out those A's and B's and C's and D's? As we've seen, what we're not accomplishing is meaningfully measuring student potential. On the other hand, what we're doing very effectively is labeling kids, squeezing them into categories, defining and often limiting their futures.

. . .

Let's stay for a moment with this notion of differentness when it comes to problem-solving. Isn't this simply another way of defining creativity? In my view, that's exactly what it is, and the troubling fact is that our current system of testing and grading tends to filter out the creative, different-thinking people who are most likely to make major contributions to a field.

. . .

The truth is that anything significant that happens in math, science, or engineering is the result of heightened intuition and creativity. The is art by another name, and it's something that tests are not very good at identifying or measuring. The skills and knowledge that tests can measure are merely warm-up exercises.

. . .

The danger of using assessments as reasons to filter out students, then, is that we may overlook or discourage those whose talents are of a different order--whose intelligence tends more to the oblique and the intuitive. At the very least, when we use testing to exclude, we run the risk of squelching creativity before it has a chance to develop.

. . .

On the other hand, when homework is demanding and meaningful, some students, at least, appreciate the difference. One high school junior commendted in the Times blog that "at my old school, I got a lot more homework. At my new prep school I get less. The difference: I spend much more time on my homework at my current school because it is harder. I feel as if I actually accomplish something with the harder homework."

This sentiment was echoed by the same seventh grader who complained about being up until midnight every night. "We should be getting harder work, not more work!"

. . .

But the more interesting question is why we have adopted this pile-it-on mentality in the first place. There is a swinging pendulum when it comes to attitudes about homework, and that pendulum has been in more or less constant motion for at least a hundred years. At the dawn of the twentieth century, the main purpose of homework was thought to be "training the mind" for the largely clerical, repetitive kinds of job that the trend toward urbanization and office work required; thus the emphasis was on memory drills, pattern recognition, rules of grammar--things that disciplined the mind but did not necessarily expand it.

. . .

For many if not most families, time together has become an increasingly rare and precious commodity. Moms work. Adults travel on business. Kids confront an ever wider array of distractions and so-called social media whose net effect, ironically enough, is to make people less social, more head-down on their keyboards and keypads.

. . .

So then, is doing homework really the best use of time that families might otherwise spend just being together? Studies suggest otherwise. One large survey conducted by the University of Michigan concluded that the single strongest predictor of better achievement scores and fewer behavioral problems was not time spent on homework, but rather frequency and duration of family meals. If we think about it, this really shouldn't be surprising. When families actually sit down and talk--when parents and children exchange ideas and truly show an interest in each other--kids absorb values, motivation, self-esteem; in short, they grow in exactly those attributes and attitudes that will make them enthusiastic and attentive learners. This is more important than mere homework.

. . .

Even with the homework help is indirect, households with books and families with a tradition of educational success have an unfair edge. Wealthier kids are less likely to be burdened with after-school jobs or chores that single parents--or exhausted parents--can't perform. In short, homework contributes to an unlevel playing field in which, educationally speaking, the rich get richer and poor get poorer.

. . .

As we've seen, students learn at different rates. Attention spans tend to max out at around fifteen minutes. Active learning creates more durable neural pathways than passive learning. Yet the passive in-class lecture--in which the entire class is expected to absorb information at the same rate, for fifty minutes or an hour, while sitting still and silent in their chairs--remains our dominant teaching mode. This results in the majority of students being lost or bored at any given time, even when there is a great lecturer.

. . .

First, I believe that the primary reason why most students don't complete their homework is frustration. They don't understand the material and no one is there to help and give feedback.

. . .

Now like everyone else involved in our education debates, I feel that money devoted to learning is money well spent--especially compared to the vast sums of squandered on military contracting, farm subsidies, bridges to nowhere, and so forth. Still, waste in certain areas of our public life does not justify waste in others, and the sad truth is that a significant part of what we spend on education is just that--waste. We spend lavishly but not wisely. We obsess about more because we cannot envision or agree about better.

. . .

For example, student/teacher ration is important. Obviously, the fewer students per teacher, the more attention each student will get. But isn't the student-to-valuable-time-with-the-teacher ratio important? I have sat in eight-person college seminars where I never had a truly meaningful interaction with the professor; I have been in thirty-person classrooms where the teacher took a few minutes to work with me and mentor me directly on a regular basis.

. . .

What will make this goal attainable is the enlightened use of technology. Let me stress ENLIGHTENED use. Clearly, I believe that technology-enhanced teaching and learning is our best chance for an affordable and equitable educational future. But the key question is how the technology is used. It's not enough to put a bunch of computers and smartboards into classrooms. The idea is to integrate the technology into how we teach and learn; without meaningful and imaginative integration, technology in the classroom could turn out to be just one more very expensive gimmick.

. . .

So the next step in the refinement of the software was to devise a hierarchy or web of concepts--the "knowledge map" we've already seen--so that the system itself could advise students what to work on next.

. . .

I eventually formed the conviction that my cousins--and all students--needed higher expectations to be placed on them. Eighty or 90 percent is okay, but I wanted them to work on things until they could get ten right answers in a row. That may sound radical or overidealistic or just too difficult, but I would argue that it was the only simple standard that was truly respectful of both the subject matter and the students. (We have refined the scoring details a good bit since then, but the basic philosophy hasn't changed.) It's demanding, yes. But it doesn't set students up to fail; it sets them up to succeed--because they can keep trying until they reach this high standard.

I happen to believe that every student, given the tool and the help that he or she needs, can reach this level of proficiency in basic match and science. I also believe it is a disservice to allow students to advance without this level of proficiency because they'll fall on their faces sometime later.

. . .

In particular, she was spending inordinate amount of time wrestling with the concepts of adding and subtracting negative numbers; she was about stuck as stuck could get. Then something clicked. I don't know exactly how it happened, and neither did her classroom teacher; that's part of the wonderful mystery of human intelligence.

. . .

They asked me to write a proposal for what I would do with $2 million; nothing to involved; two pages would do. A million dollars per page; not bad. Keep in mind that up to this point I had spend a grand total of about $2,000 on the Khan Academy.

. . .

In itself this was not so unusual. Many people had already donated $5, $10, and even $100 at a time over PayPal. But this time a check for $10,000 arrived in the mail. The sender was named Ann Doerr. After a little frantic web research, I realized that Ann was the wife of famed venture caplitalist John Doerr. I sent her an email thanking her for her generous support, and she wrote back suggesting we have lunch.

We agreed to meet in May in downtown Palo Alto. Ann arrived on a green-blue bicycle. We talked about what Khan Academy could be. When Ann asked how I was supporting myself and my family, I answered, trying not to sound too desperate, "I'm not; we're living off of savings." She nodded and we each went our way.

About twenty minutes later, I got a text message I was parking in my driveway. It was from Ann: You need to support yourself. I am sending a check for $100,000 right now.

I almost crashed into the garage door.

. . .

Anyone who stops learning is old, whether twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning stays young. The greatest thing in life is to keep your mind young.

--Henry Ford

It is utterly false and cruelly arbitrary to put all the play and learning into childhood, all the work into middle age, and all the regrets into old age.

--Margaret Mead

. . .

New knowledge becomes a smaller and smaller part of the mix. The problem is that as the pace of change accelerates all around us, the ability to learn new things may be the most important skill of all. Is it realistic to expect adults to be able to do this?

The answer is resounding yes. According to a recent paper issued by the Royal Society of London, "the brain has extraordinary adaptability, sometimes referred as 'neuroplasticity.' This is due to the process by which connections between neurons are strengthened when they are simultaneously activated; often summarized as, 'neurons that fire together wire together.' The effect is known as experience-dependent plasticity and is present throughout life."

. . .

On the other hand, adults seem to be better at learning by association. Weith a bigger knowledge base to begin with, and long-established habits of logic and deduction, grown-ups are more likely to grasp new concepts by way of their connections to ideas already known.

. . .

The certainty of change, coupled with the complete uncertainty as to the precise nature of the change, has profound and complex implications for our approach to education. For me, though, the most basic takeaway is crystal clear: Since we can't predict exactly what today's young people will need to know in ten or twenty years, what we teach them is less important than how they learn to teach themselves.

. . .

Coming back to MIT, Shantanu and I did take something close to double course load, and we both graduated with high honor GPAs and multiple degrees. And it wasn't because we were any smarter or harder-working than our peers. It was because we didn't waste time sitting passively in class.

. . .

To state what should be obvious, there is nothing natural about segregating kids by age.

. . .

In fact, the only way to do it would be to make clear that what happens in the classroom is but preparation for real competition in the outside world. That the exams aren't there to label and humiliate you; they are there to fine-tune your abilities. That when you identified deficiencies, it doesn't mean that you are dumb; it means that you have something to work on.

. . .

As everyone knows, it's easier to keep pedaling a bicycle than to start one again after a stop; why should the process be any different with learning?

In point of fact, however, the most serious downside of summer vacation isn't just that kids stop learning; it's that they almost immediately start unlearning.

. . .

But I note that I say preparedness, not potential! Well-designed tests can give a pretty solid idea of what a student has learned, but only a very approximate picture of what she can learn. To put in a slightly different way, tests tend to measure quantities of information (and sometimes knowledge) rather than quality of minds--not to mention character.

. . .

First, I would eliminate letter grades altogether. In a system based on mastery learning, there is no need and no place for them. Students advance only when they demonstrate clear proficiency with a concept, as measured either by the ten-in-a-row heuristic or some future refinement of it. Since no one is pushed ahead (or left behind) until proficiency is reached, the only possible grade would be an A. To paraphrase Garrison Keillor, all the kids would be way above average, so grades would be pointless.

. . .

For one thing, Waterloo recognized the value of internships long ago (they call them co-ops) and has made them an integral part of students' experience. By graduation, a typical Waterloo grad will have spent six internships lasting a combined twenty-four months at a major companies--often American. The typical American grad will have spent about thirty-six months in lecture halls and a mere three to six months in internships.

. . .

The school I envision would embrace technology not for its own sake, but as a means to improve deep conceptual understanding, to make quality, relevant education far more portable, and--somewhat counterintuitively--to humanize the classroom. It would raise both the status and the morale of teachers by freeing them from drudgery and allowing them more time to teach, to help. It would give students more independence and control, allowing them to claim true ownership of their educations. By mixing ages and encouraging peer-to-peer tutoring, his schoolhouse would give adolescents the chance to begin to take on adult responsibilities.

. . .

Lessons aimed at thorough master of concepts--interrelated concepts--would proceed in harmony with the way our brains are actually wired, and would prepare students to function in a complex world where good enough no longer is.

. . .

Sunday, June 14, 2015

the life-changing magic of tidying up

Short notes collected from Marie Kondo's beautiful book--the life-changing magic of tidying up, the Japanese art of decluttering and organizing.

Tidying is just a tool, not the final destination. The true goal should be to establish the lifestyle you want most once your house has been put in order.

Putting things away creates the illusion that the clutter problem has been solved. But sooner or later, all the storage units are full, the room once again overflows with things, and some new and "easy" storage method becomes necessary, creating a negative spiral. This is why tidying must start with discarding. We need to exercise self-control and resist storing our belongings until we have finished identifying what we really want and need to keep.

Tidying up by location is fatal mistake. I recommend tidying by category. For example, instead of deciding that today you'll tidy a particular room, set goals like "clothes today, books tomorrow."

Effective tidying involves only two essential actions: discarding and deciding where to store things. Of the two, discarding must come first.

I never tidy my room. Why? Because it is already tidy.

Through this experience, I came to conclusion that the best way to choose what to keep and what to throw away is to take each item in one's hand and ask: "Does it spark joy?" If it does, keep it. If not, dispose of it.

To quietly work away at disposing of your own excess is actually the best way of dealing with a family that doesn't tidy. As if drawn into your wake, they will begin weeding out unnecessary belongings and tidying without your having to utter a single complaint. It may sound incredible, but when someone starts tidying it sets off a chain reaction.

If you feel annoyed with your family for being untidy, I urge you to check your own space, especially your storage. You are bound to find things that need to be thrown away. The urge to point out someone else's failure to tidy is usually a sign that you are neglecting to take care of your own space. This is why you should begin by discarding only your own things. You can leave the communal spaces to the end. The first step is to confront your own stuff.

If sweatpants are your everyday attire, you'll end up looking like you belong in them, which is not very attractive. What you wear in the house does impact your self-image.

The key is to store things standing up rather than laid flat.

Recently, I have noticed that having fewer books actually increases the impact of the information I read. I recognize necessary information much more easily. Many of clients, particularly those who have disposed of a substantial number of books and papers, have also mentioned this. For books, timing is everything. The moment you first encounter a particular book is the right time to read it. To avoid missing that moment, I recommend that you keep your collection small.

The reason every item must have a designated place is because the existence of an item without a home multiplies the chances that your space will become cluttered again.

The secret to maintaining an uncluttered room is to pursue ultimate simplicity in storage so that you can tell at a glance how much you have.

For the reasons described above, my storage method is extremely simple. I have only two rules: store all items of the same type in the same place and don't scatter storage space.

If you live with your family, first clearly define separate storage spaces for each of family member. This is essential. For example, you can designate separate closets for you, your husband, and your children, and store whatever belongs to each person in his or her respective closet. That's all you need to do. The important points here is to designate only one place per person if at all possible. In other words, storage should be focused in one spot. If storage places are spread around, the entire house will become cluttered in no time. To concentrate the belongings of each person in one spot is the most effective way for keeping storage tidy.

Clutter is caused by a failure to return things to where they belong. Therefore, storage should reduce the effort needed to put things away, not the effort needed to get them out.

I store things vertically and avoid stacking for two reasons. First, if you stack things, you end up with what seems like inexhaustible storage space. Things can be stacked forever and endlessly on top, which makes it harder to notice the increasing volume. In contrast, when things are stored vertically, any increase takes up space and you will eventually run out of storage area. When you do, you'll notice, "Ah, I'm starting to accumulate stuff again."

The other reason is this: stacking is very hard on the things at the bottom. When things are piled on top of one another, the things underneath get squished. Stacking weakens and exhausts the things that bear the weight of the pile.

Spaces that are out of sight are still part of your house. By eliminating excess visual information that doesn't inspire joy, you can make your space much more peaceful and comfortable. The difference this makes is so amazing it would be a waste not to try it.

Tidying is just a tool, not the final destination. The true goal should be to establish the lifestyle you want most once your house has been put in order.

. . .

Putting things away creates the illusion that the clutter problem has been solved. But sooner or later, all the storage units are full, the room once again overflows with things, and some new and "easy" storage method becomes necessary, creating a negative spiral. This is why tidying must start with discarding. We need to exercise self-control and resist storing our belongings until we have finished identifying what we really want and need to keep.

. . .

Tidying up by location is fatal mistake. I recommend tidying by category. For example, instead of deciding that today you'll tidy a particular room, set goals like "clothes today, books tomorrow."

. . .

Effective tidying involves only two essential actions: discarding and deciding where to store things. Of the two, discarding must come first.

. . .

I never tidy my room. Why? Because it is already tidy.

. . .

Through this experience, I came to conclusion that the best way to choose what to keep and what to throw away is to take each item in one's hand and ask: "Does it spark joy?" If it does, keep it. If not, dispose of it.

. . .

To quietly work away at disposing of your own excess is actually the best way of dealing with a family that doesn't tidy. As if drawn into your wake, they will begin weeding out unnecessary belongings and tidying without your having to utter a single complaint. It may sound incredible, but when someone starts tidying it sets off a chain reaction.

. . .

If you feel annoyed with your family for being untidy, I urge you to check your own space, especially your storage. You are bound to find things that need to be thrown away. The urge to point out someone else's failure to tidy is usually a sign that you are neglecting to take care of your own space. This is why you should begin by discarding only your own things. You can leave the communal spaces to the end. The first step is to confront your own stuff.

. . .

If sweatpants are your everyday attire, you'll end up looking like you belong in them, which is not very attractive. What you wear in the house does impact your self-image.

. . .

The key is to store things standing up rather than laid flat.

. . .

Recently, I have noticed that having fewer books actually increases the impact of the information I read. I recognize necessary information much more easily. Many of clients, particularly those who have disposed of a substantial number of books and papers, have also mentioned this. For books, timing is everything. The moment you first encounter a particular book is the right time to read it. To avoid missing that moment, I recommend that you keep your collection small.

. . .

The reason every item must have a designated place is because the existence of an item without a home multiplies the chances that your space will become cluttered again.

. . .

The secret to maintaining an uncluttered room is to pursue ultimate simplicity in storage so that you can tell at a glance how much you have.

. . .

For the reasons described above, my storage method is extremely simple. I have only two rules: store all items of the same type in the same place and don't scatter storage space.

. . .

If you live with your family, first clearly define separate storage spaces for each of family member. This is essential. For example, you can designate separate closets for you, your husband, and your children, and store whatever belongs to each person in his or her respective closet. That's all you need to do. The important points here is to designate only one place per person if at all possible. In other words, storage should be focused in one spot. If storage places are spread around, the entire house will become cluttered in no time. To concentrate the belongings of each person in one spot is the most effective way for keeping storage tidy.

. . .

Clutter is caused by a failure to return things to where they belong. Therefore, storage should reduce the effort needed to put things away, not the effort needed to get them out.

. . .

I store things vertically and avoid stacking for two reasons. First, if you stack things, you end up with what seems like inexhaustible storage space. Things can be stacked forever and endlessly on top, which makes it harder to notice the increasing volume. In contrast, when things are stored vertically, any increase takes up space and you will eventually run out of storage area. When you do, you'll notice, "Ah, I'm starting to accumulate stuff again."

The other reason is this: stacking is very hard on the things at the bottom. When things are piled on top of one another, the things underneath get squished. Stacking weakens and exhausts the things that bear the weight of the pile.

. . .

Spaces that are out of sight are still part of your house. By eliminating excess visual information that doesn't inspire joy, you can make your space much more peaceful and comfortable. The difference this makes is so amazing it would be a waste not to try it.

. . .

Monday, April 27, 2015

The People Store

An excellent essay from Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister's marvelous book - Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams.

In a production environment, it's convenient to think of people as parts of the machine. When a part wears out, you get another. The replacement part is interchangeable with the original. You order a new one, more or less, by number.

Many development managers adopt the same attitude. They go to great lengths to convince themselves that no one is irreplaceable. Because they fear that a key person will leave, they force themselves to believe that there is no such thing as a key person. Isn't that the essence of management, after all, to make sure the work goes on whether the individuals stay or not? They act as though there were a magical People Store they could call up and say, "Send me a new George Gandenhyer, but make him a little less uppity."