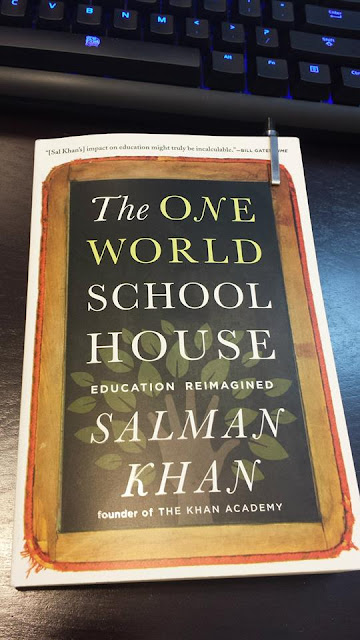

Personal notes collected from a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful work and great thought distillation from Salman Khan: The One World School House--Education ReImagined.

We are still in the early stage of an inflection point that I believe is the most consequential in history: the Information Revolution. And in this revolution, the pace of change is swift that deep creativity and analytical thinking are no longer optional; they not luxuries but survival skills.

. . .

I'd had plenty of professors who knew their subject cold but simply weren't good at sharing what they knew. I believed, and still believe, that teaching is a separate skill--in fact, an art that is creative, intuitive, and highly personal.

But it isn't only an art. It has, or should have, some of the rigor of science as well.

. . .

Unfortunately, however, the idea that smaller classes alone will magically solve the problem of students being left behind is fallacy.

It ignores several basic facts about how people actually learn. People learn at different rates. Some people seem to catch on to things quick bursts of intuition; others grunt and grind their way toward comprehension. Quicker isn't necessarily smarter and slower definitely isn't dumber. Further, catching on quickly isn't the same as understanding thoroughly. So the pace of learning is a question of style, not relative intelligence. The tortoise may very well end up with more knowledge--more useful, lasting knowledge--than the hare.

Moreover, a student who is slow at learning arithmetic may be off the charts when it comes to the abstract creativity needed in higher mathematics. The point is that whether there are ten or twenty kids in a class, there will be disparities in their grasp of a topic at any given time. Even a one-to-one ratio is not ideal if the teacher feels forced to march the student along at a state-mandated pace, regardless of how well the concepts are understood. When that rather arbitrary "snapshot" moment comes along--when it's time to wrap up the module, give the exam, and move on--there will still like be some students who haven't quite figured things out.

They could probably figure things out eventually--but that's exactly the problem. The standard classroom model doesn't really allow for eventual understanding. The class--of whatever size--has moved on.

. . .

I was starting to get seriously concerned that perhaps I was doing Nadia more harm than good. With nothing but kind inventions, I was causing her a lot of discomfort and anxiety. My hope had been to restore her confidence; maybe I was damaging it still further.

This forced me to acknowledge that sometimes the presence of a teacher--either in the room or at the other end of a telephone connection; either in a class of thirty or tutoring one-to-one--can be a source of student paralysis. From the teacher's perspective, what's going on is a helping relationship; but from the student's point of view, it's difficult if not impossible to avoid an element of confrontation. A question is asked; an answer is expected immediately; that brings pressure. The student doesn't want to disappoint the teacher. She fears she will be judged. And all these factors interfere with the student's ability to fully concentrate on the matter at hand. Even more, students are embarassed to communicate what they do and do and do not understand.

. . .

In a traditional academic model, the time allotted to learn something is fixed while the comprehension of the concept is variable. Washburne was advocating the opposite. What should be fixed is a high level of comprehension and what should be variable is the amount of time students have to understand a concept.

. . .

Stressing passivity over activity is one such misstep. Another, equally important, is the failure of standard education to maximize brain's capacity for associative learning--the achieving of deeper comprehension and more durable memory by relating something newly learned to something already known.

. . .

As Kandel writes, "For a memory to persist, the incoming information must be thoroughly and deeply processed. This is accomplished by attending to the information and associating it meaningfully systematically with knowledge already well established in memory."

In other words, it's easier to understand and remember something if we can relate it to something else we already know. This is why it's easier to memorize a poem than a series of non-sense syllables of equal length. In a poem, each word relates to images in our minds and to what has come before; there are rules of rhythm and connection that we understand, even if subliminally, the poem must follow. Rather than memorizing individual bits of information, we are dealing with patterns and strands of logic that allow us to come closer to seeing something whole.

. . .

The possibilities are endless, but they can't be realized given the balkanizing habits of our current system. Even within the already sawed-off classes, content is chunked into stand-alone episodes, and the connections are severed. In algebra, for example, students are taught to memorize the formula for the vertex of a parabola. Then they separately memorize the quadratic formula. In yet another lesson, they probably learn to "complete the square." The reality, however, is that all those formulas are expressions of essentially the same mathematical logic, so why aren't they taught together as the multiple facets of the same concept?

I am not just nitpicking here. I believe that the breaking up of concepts like these has profound and even crucial consequences for how deeply students lean and how well they remember it. It is the connections among concepts--or the lack of connections--that separate the students who memorize a formula for an exam only to forget it the next month and the same students who internalize the concepts and are able to app-ly them when they need them a decade later.

. . .

The heavy baggage of the current academic model has become increasingly apparent recently, as economic realities no longer favor a docile and disciplined working class with just the basic proficiencies in reading, math, and the liberal arts. Today's world needs a workforce of creative, curious, and self-directed lifelong learners who are capable of conceiving and implementing novel ideas. Unfortunately, this is the type of student that the Prussian model suppresses.

. . .

Let's consider a few things about that inevitable test. What constitutes a passing grade? In most classrooms in most schools, students pass with 75 or 80 percent. This is customary. But if you think about it even for a moment, it's unacceptable if not disastrous. Concepts build on one another. Algebra requires arithmetic. Trigonometry flows from geometry. Calculus and physics call for all of the above. A shaky understanding early on will lead to complete bewilderment later. And yet we blithely give out passing grades for test scores of 75 or 80. For many teachers, it may seem like a kindness or perhaps merely an administrative necessity to pass these marginal students. In effect, it is a disservice and a lie. We are telling students they've learned something that they really haven't learned. We wish them and nudge them ahead to the next, more difficult unit, for which they have not been properly prepared. We are setting them up to fail.

. . .

She's been a "good" math student all along, but all of a sudden, no matter how much she studies and how good her teacher is, she has trouble comprehending what is happening in class.

How is this possible? She's gotten A's. She's been in the top quintile of her class. And yet her preparation lets her down. Why? The answer is that our student has been a victim of Swiss cheese learning. Though it seems solid from outside, her education is full of holes.

. . .

Once a certain level of proficiency is obtained, the learner should attempt to teach the subject to other students so that they themselves develop a deeper understanding. As they progress, they should keep revisiting the core ideas through the lenses of different, active experiences. That's the way to get the holes out of Swiss cheese learning. It is, after all, much better and much more useful to have a deep understanding of algebra than a superficial understanding of algebra, trigonometry, and calculus. Students with deep backgrounds in algebra find calculus intuitive.

. . .

The example of the historically good student all of a sudden not understanding an advanced class because of Swiss cheese foundation could best be termed hitting a wall. And it is commonplace. We have all seen classmates go through this and have directly experienced it ourselves. It's a horrible feeling, leaving the student only frustration and helplessness.

. . .

But absent a firm grasp of the basics, organic chemistry doesn't feel intuitive at all; rather, it seems like a daunting dizzying, and endless progression of reactions that need to be memorized. Faced with such a mind-numbing chore, many students give up. Some, by superhuman effort, power through. The problem is that memorization without intuitive understanding can't remove the wall, but only push it back.

. . .

Calculus has the power to solve problems that are beyond the reach of more elementary forms of math, but unless you've truly understood those more elementary concepts, calculus of no use to you. It's this element of synthesis, of pulling it all together, that gives calculus its beauty. At the same time, however, it's why calculus is so likely to reveal the cracks in people's math foundations. In stacking concepts upon concept, calculus is the subject most likely to tip the balance, reveal the dry rot, and send the whole edifice crashing down.

. . .

Now, I tell this story not to embarrass or criticize the CFO. He was a bright guy with Ivy League education, and his math background extended to calculus and beyond. Clearly though, there seemed to be something wrong, something missing, in the way that he'd been taught. He'd apparently studied algebra with an eye toward getting a good grade on the test that was the climax of the unit; presumably the test centered on the working out of a handful problems, and the problems consisted of solving for variables that had no apparent meaning in the real world. What, then, was the point of learning algebra? What was algebra about? What could algebra do? There very basic questions, it seemed, had gone unexplored.

This failure to relate classroom topics to their eventual application in the real world is one of the central shortcomings of our broken classroom model, and is a direct consequence of our habit of rushing through conceptual modules and pronouncing them finished when in fact only a very shallow level of functional understanding has been reached. What do most kids actually take away from algebra? Sadly, the usual takeaway is that it's about a bunch of x's and y's, and that if you plug in a few formulas and procedures that you've learned by rote, you'll come up with the answer.

But the power and importance of algebra is not to be found in x's and y's on a test paper. The important and wonderful diverse set of phenomena and ideas. The same equations that I used to figure out the production costs of a public company could be used to calculate the momentum of a particle in space. The same equations can model both the optimal path of a projectile and the optimal price for a new product. The same ideas that govern the changes of inheriting a disease also informs whether it makes sense to go for a first down on fourth-and-inches.

The difficulty, of course, is that getting to this deeper, functional understanding would use up valuable class time that might otherwise be devoted to preparing for a test. So most students, rather than appreciating algebra as a keen and versatile tool for navigating through the world, see it as one more hurdle to be passed, a class rather than a gateway. The learn it, sort of, then push it aside to make room for the lesson to follow.

. . .

For all of that, conventional schools tend to place great emphasis on test results as a measure of a student's innate ability or potential--not only on standardized tests, but on thoroughly unstandardized end-of-term exams that may or may not be well designed--and this has very serious consequences. What are we actually accomplishing when we hand out those A's and B's and C's and D's? As we've seen, what we're not accomplishing is meaningfully measuring student potential. On the other hand, what we're doing very effectively is labeling kids, squeezing them into categories, defining and often limiting their futures.

. . .

Let's stay for a moment with this notion of differentness when it comes to problem-solving. Isn't this simply another way of defining creativity? In my view, that's exactly what it is, and the troubling fact is that our current system of testing and grading tends to filter out the creative, different-thinking people who are most likely to make major contributions to a field.

. . .

The truth is that anything significant that happens in math, science, or engineering is the result of heightened intuition and creativity. The is art by another name, and it's something that tests are not very good at identifying or measuring. The skills and knowledge that tests can measure are merely warm-up exercises.

. . .

The danger of using assessments as reasons to filter out students, then, is that we may overlook or discourage those whose talents are of a different order--whose intelligence tends more to the oblique and the intuitive. At the very least, when we use testing to exclude, we run the risk of squelching creativity before it has a chance to develop.

. . .

According to a journal article called "Teacher Assessment of Homework," by a researcher named Stephen Alioa, the rather surprising fact was that "most teachers do not take courses specifically on homework during teacher training." Lesson plans, yes; techniques for guiding classroom activities, yes; homework, no. It's as if homework is an afterthought, some strange gray area that is still the responsibility of students but not so much for teachers. According to Harris Cooper, author of The Battle over Homework, when it comes to crafting homework assignments, "most teachers are winging it." No wonder homework is sometimes seen by students--and parents--as a tedious waste of time.

On the other hand, when homework is demanding and meaningful, some students, at least, appreciate the difference. One high school junior commendted in the Times blog that "at my old school, I got a lot more homework. At my new prep school I get less. The difference: I spend much more time on my homework at my current school because it is harder. I feel as if I actually accomplish something with the harder homework."

This sentiment was echoed by the same seventh grader who complained about being up until midnight every night. "We should be getting harder work, not more work!"

. . .

But the more interesting question is why we have adopted this pile-it-on mentality in the first place. There is a swinging pendulum when it comes to attitudes about homework, and that pendulum has been in more or less constant motion for at least a hundred years. At the dawn of the twentieth century, the main purpose of homework was thought to be "training the mind" for the largely clerical, repetitive kinds of job that the trend toward urbanization and office work required; thus the emphasis was on memory drills, pattern recognition, rules of grammar--things that disciplined the mind but did not necessarily expand it.

. . .

For many if not most families, time together has become an increasingly rare and precious commodity. Moms work. Adults travel on business. Kids confront an ever wider array of distractions and so-called social media whose net effect, ironically enough, is to make people less social, more head-down on their keyboards and keypads.

. . .

So then, is doing homework really the best use of time that families might otherwise spend just being together? Studies suggest otherwise. One large survey conducted by the University of Michigan concluded that the single strongest predictor of better achievement scores and fewer behavioral problems was not time spent on homework, but rather frequency and duration of family meals. If we think about it, this really shouldn't be surprising. When families actually sit down and talk--when parents and children exchange ideas and truly show an interest in each other--kids absorb values, motivation, self-esteem; in short, they grow in exactly those attributes and attitudes that will make them enthusiastic and attentive learners. This is more important than mere homework.

. . .

Even with the homework help is indirect, households with books and families with a tradition of educational success have an unfair edge. Wealthier kids are less likely to be burdened with after-school jobs or chores that single parents--or exhausted parents--can't perform. In short, homework contributes to an unlevel playing field in which, educationally speaking, the rich get richer and poor get poorer.

. . .

As we've seen, students learn at different rates. Attention spans tend to max out at around fifteen minutes. Active learning creates more durable neural pathways than passive learning. Yet the passive in-class lecture--in which the entire class is expected to absorb information at the same rate, for fifty minutes or an hour, while sitting still and silent in their chairs--remains our dominant teaching mode. This results in the majority of students being lost or bored at any given time, even when there is a great lecturer.

. . .

First, I believe that the primary reason why most students don't complete their homework is frustration. They don't understand the material and no one is there to help and give feedback.

. . .

Now like everyone else involved in our education debates, I feel that money devoted to learning is money well spent--especially compared to the vast sums of squandered on military contracting, farm subsidies, bridges to nowhere, and so forth. Still, waste in certain areas of our public life does not justify waste in others, and the sad truth is that a significant part of what we spend on education is just that--waste. We spend lavishly but not wisely. We obsess about more because we cannot envision or agree about better.

. . .

For example, student/teacher ration is important. Obviously, the fewer students per teacher, the more attention each student will get. But isn't the student-to-valuable-time-with-the-teacher ratio important? I have sat in eight-person college seminars where I never had a truly meaningful interaction with the professor; I have been in thirty-person classrooms where the teacher took a few minutes to work with me and mentor me directly on a regular basis.

. . .

What will make this goal attainable is the enlightened use of technology. Let me stress ENLIGHTENED use. Clearly, I believe that technology-enhanced teaching and learning is our best chance for an affordable and equitable educational future. But the key question is how the technology is used. It's not enough to put a bunch of computers and smartboards into classrooms. The idea is to integrate the technology into how we teach and learn; without meaningful and imaginative integration, technology in the classroom could turn out to be just one more very expensive gimmick.

. . .

So the next step in the refinement of the software was to devise a hierarchy or web of concepts--the "knowledge map" we've already seen--so that the system itself could advise students what to work on next.

. . .

I eventually formed the conviction that my cousins--and all students--needed higher expectations to be placed on them. Eighty or 90 percent is okay, but I wanted them to work on things until they could get ten right answers in a row. That may sound radical or overidealistic or just too difficult, but I would argue that it was the only simple standard that was truly respectful of both the subject matter and the students. (We have refined the scoring details a good bit since then, but the basic philosophy hasn't changed.) It's demanding, yes. But it doesn't set students up to fail; it sets them up to succeed--because they can keep trying until they reach this high standard.

I happen to believe that every student, given the tool and the help that he or she needs, can reach this level of proficiency in basic match and science. I also believe it is a disservice to allow students to advance without this level of proficiency because they'll fall on their faces sometime later.

. . .

In particular, she was spending inordinate amount of time wrestling with the concepts of adding and subtracting negative numbers; she was about stuck as stuck could get. Then something clicked. I don't know exactly how it happened, and neither did her classroom teacher; that's part of the wonderful mystery of human intelligence.

. . .

They asked me to write a proposal for what I would do with $2 million; nothing to involved; two pages would do. A million dollars per page; not bad. Keep in mind that up to this point I had spend a grand total of about $2,000 on the Khan Academy.

. . .

In itself this was not so unusual. Many people had already donated $5, $10, and even $100 at a time over PayPal. But this time a check for $10,000 arrived in the mail. The sender was named Ann Doerr. After a little frantic web research, I realized that Ann was the wife of famed venture caplitalist John Doerr. I sent her an email thanking her for her generous support, and she wrote back suggesting we have lunch.

We agreed to meet in May in downtown Palo Alto. Ann arrived on a green-blue bicycle. We talked about what Khan Academy could be. When Ann asked how I was supporting myself and my family, I answered, trying not to sound too desperate, "I'm not; we're living off of savings." She nodded and we each went our way.

About twenty minutes later, I got a text message I was parking in my driveway. It was from Ann: You need to support yourself. I am sending a check for $100,000 right now.

I almost crashed into the garage door.

. . .

Anyone who stops learning is old, whether twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning stays young. The greatest thing in life is to keep your mind young.

--Henry Ford

It is utterly false and cruelly arbitrary to put all the play and learning into childhood, all the work into middle age, and all the regrets into old age.

--Margaret Mead

. . .

New knowledge becomes a smaller and smaller part of the mix. The problem is that as the pace of change accelerates all around us, the ability to learn new things may be the most important skill of all. Is it realistic to expect adults to be able to do this?

The answer is resounding yes. According to a recent paper issued by the Royal Society of London, "the brain has extraordinary adaptability, sometimes referred as 'neuroplasticity.' This is due to the process by which connections between neurons are strengthened when they are simultaneously activated; often summarized as, 'neurons that fire together wire together.' The effect is known as experience-dependent plasticity and is present throughout life."

. . .

On the other hand, adults seem to be better at learning by association. Weith a bigger knowledge base to begin with, and long-established habits of logic and deduction, grown-ups are more likely to grasp new concepts by way of their connections to ideas already known.

. . .

The certainty of change, coupled with the complete uncertainty as to the precise nature of the change, has profound and complex implications for our approach to education. For me, though, the most basic takeaway is crystal clear: Since we can't predict exactly what today's young people will need to know in ten or twenty years, what we teach them is less important than how they learn to teach themselves.

. . .

Coming back to MIT, Shantanu and I did take something close to double course load, and we both graduated with high honor GPAs and multiple degrees. And it wasn't because we were any smarter or harder-working than our peers. It was because we didn't waste time sitting passively in class.

. . .

To state what should be obvious, there is nothing natural about segregating kids by age.

. . .

In fact, the only way to do it would be to make clear that what happens in the classroom is but preparation for real competition in the outside world. That the exams aren't there to label and humiliate you; they are there to fine-tune your abilities. That when you identified deficiencies, it doesn't mean that you are dumb; it means that you have something to work on.

. . .

As everyone knows, it's easier to keep pedaling a bicycle than to start one again after a stop; why should the process be any different with learning?

In point of fact, however, the most serious downside of summer vacation isn't just that kids stop learning; it's that they almost immediately start unlearning.

. . .

But I note that I say preparedness, not potential! Well-designed tests can give a pretty solid idea of what a student has learned, but only a very approximate picture of what she can learn. To put in a slightly different way, tests tend to measure quantities of information (and sometimes knowledge) rather than quality of minds--not to mention character.

. . .

First, I would eliminate letter grades altogether. In a system based on mastery learning, there is no need and no place for them. Students advance only when they demonstrate clear proficiency with a concept, as measured either by the ten-in-a-row heuristic or some future refinement of it. Since no one is pushed ahead (or left behind) until proficiency is reached, the only possible grade would be an A. To paraphrase Garrison Keillor, all the kids would be way above average, so grades would be pointless.

. . .

For one thing, Waterloo recognized the value of internships long ago (they call them co-ops) and has made them an integral part of students' experience. By graduation, a typical Waterloo grad will have spent six internships lasting a combined twenty-four months at a major companies--often American. The typical American grad will have spent about thirty-six months in lecture halls and a mere three to six months in internships.

. . .

The school I envision would embrace technology not for its own sake, but as a means to improve deep conceptual understanding, to make quality, relevant education far more portable, and--somewhat counterintuitively--to humanize the classroom. It would raise both the status and the morale of teachers by freeing them from drudgery and allowing them more time to teach, to help. It would give students more independence and control, allowing them to claim true ownership of their educations. By mixing ages and encouraging peer-to-peer tutoring, his schoolhouse would give adolescents the chance to begin to take on adult responsibilities.

. . .

Lessons aimed at thorough master of concepts--interrelated concepts--would proceed in harmony with the way our brains are actually wired, and would prepare students to function in a complex world where good enough no longer is.

. . .